Biography

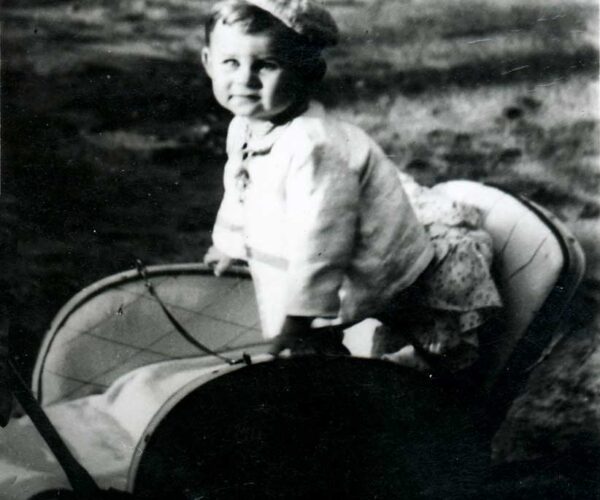

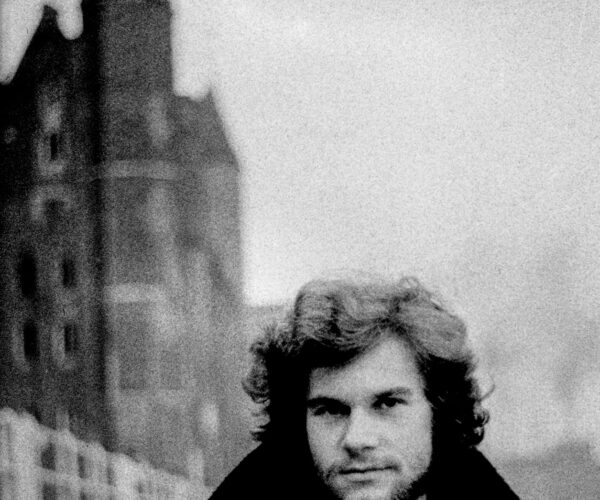

May 28, 1952

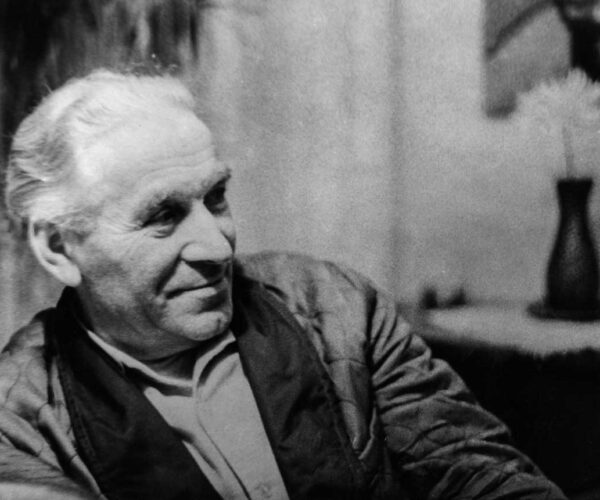

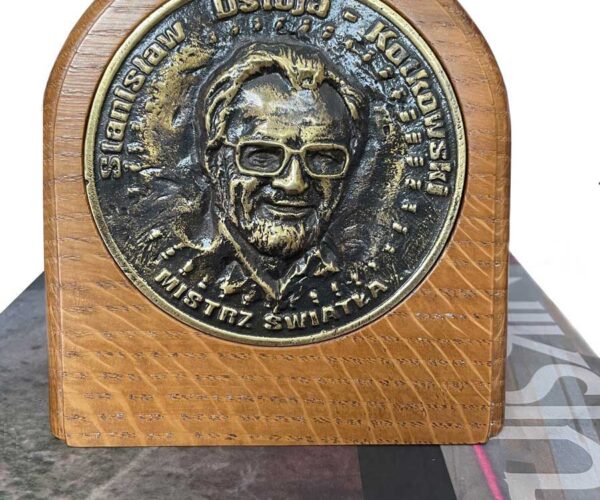

I was born in Przasnysz in a corner house at pl. 1-go Maja – later known for the fact that Stanisław Ostoja-Kotkowski was also born in the same house before the war, who after emigrating to Australia became one of the most famous artists of this continent. the Ostoja-Kotkowski medal will be awarded to the most active creators of culture from Przasnysz or its vicinity. I also received such a medal in 2020. My mother was Alina Niksińska (née Kiembrowska) – she died at the age of 81 in 2004, and my father was Antoni Niksiński, who died in 1994 when he was 71 years old. I also had a brother, Andrzej, who was 9 years older than me and is no longer alive – he died in 2012.

1958 - 1970

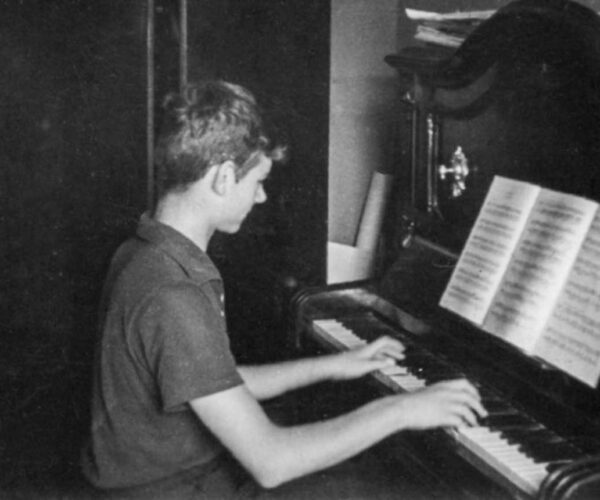

I attended Primary School No. 1 in Przasnysz, and then, in the years 1967 – 1970, to high school 36.

1970 - 1972

After matriculation, I tried twice to get into the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, but due to a lack of extra points (for good worker or peasant background) and a lack of any family connections or connections, I did not get into the academy, even though I passed all the exams with the highest marks. Escaping from being conscripted in 1970, I worked for a year as a decorator at the Military Unit in Przasnysz. And the following year I moved to Warsaw and even attended the Academy of Fine Arts in Janusz Przybylski’s studio as a free student. He (J.P.) invited me to a Plein-Air for the participants of his studio who were trying to get into the Academy of Fine Arts. This open-air workshop was held in a beautiful palace in Nieborów, where Janusz Przybylski and his assistants gave lectures on the history and theory of art, as well as painting and drawing workshops for the candidates for the Academy of Fine Arts. I developed my painting skills there to such an extent that my portfolio was rejected at the re-examination for the Academy of Fine Arts, allegedly because I was mannered and “uneducable”.

Fortunately, the examinations for the Faculty of Pedagogy with Initial Visual Education were held at a later date and could be taken after the examination for the Visual Arts Colleges. After the exam, I was admitted to the University of Gdansk at this Faculty of Pedagogy with Initial Visual Education. At that university there were a lot of “survivors” who didn’t get into various art schools in Poland and after a year almost all of us tried to get into the Academy of Fine Arts in Gdansk.

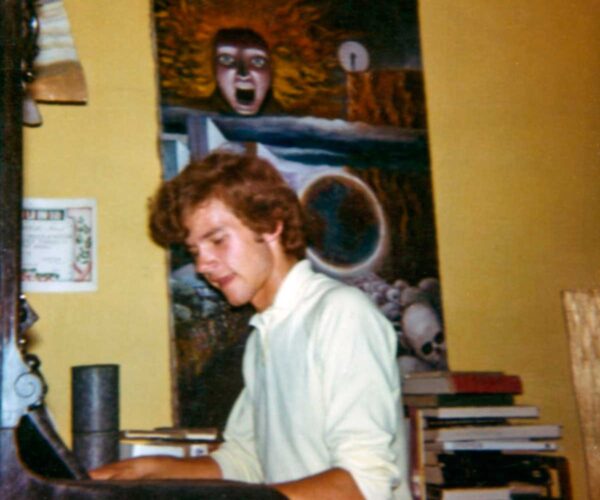

1972-1974

I applied to the Sculpture Department at the Academy of Fine Arts in Gdańsk at the urging of a friend who had already tried to get there four times. I thought that if I took the sculpture exam, I would definitely not be considered “mannered” because I had never sculpted before. To my surprise and joy, this brought a positive effect, but in September I received a letter from the PWSSP rectorate that there were not enough places at the sculpture department and I was offered a year’s study at the Graphics Department, and after a year they would transfer me back to the sculpture department. However, it was my dream to get into the Faculty of Graphic Arts, so I gladly took advantage of this offer and did not move to sculpture after that. I completed my first year in the painting studio of prof. Borowski and Lettering (Lorenczuk) and Graphic Design (Krechowicz) studios. Especially studies with prof. Lorenczuk from the practice and theory of typography influenced my love for letters and it continues to this day. The following year, I found myself in the painting studio of the outstanding painter and rector of the PWSSP, Władysław Jackiewicz. The professor was rarely in the studio, but he had two assistants – the interesting painter Teresa Miszkin and another assistant whose name I do not remember and do not want to remember. I had constant conflicts with him because he did not tolerate my inclination towards drawing and printmaking at that time. I didn’t paint much then and I had only two paintings for the exhibition at the end of the year, but a dozen or so drawings and prints. This assistant did not want to pass my year at that time, but when it turned out that my graphics in the next two years (1974 and 1975) won the main prizes in the Krakow Student Graphic Review, at the final exhibition he showed my graphic and drawing works in such an amount that paradoxically, I had the most works at this exhibition. However, the deepening conflict with this assistant made me apply for a transfer to the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. Then it turned out that his letter from the Academy of Fine Arts in Gdańsk had reached Warsaw, saying that I was an irresponsible, quarrelsome and anti-social student.

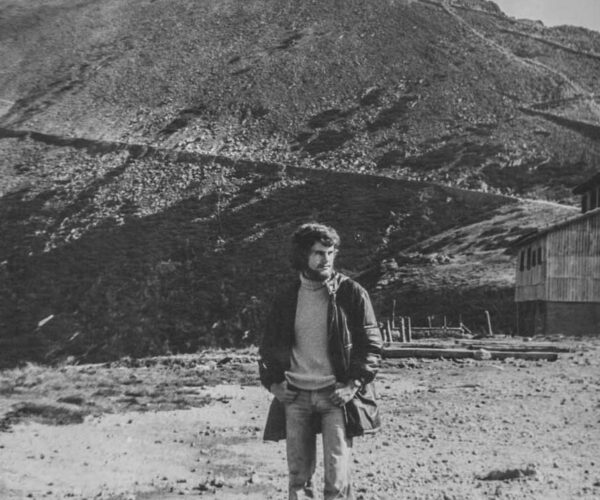

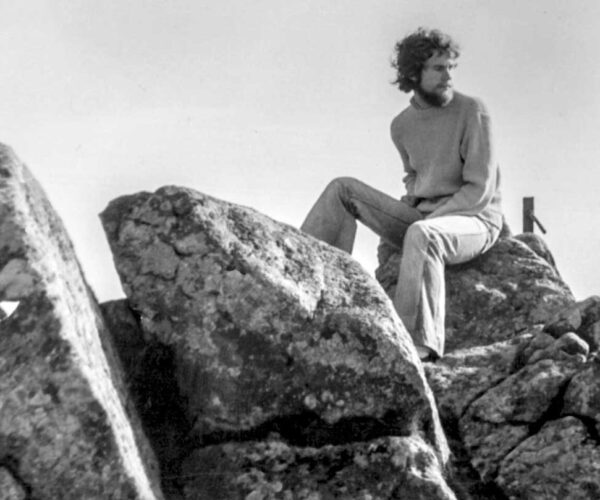

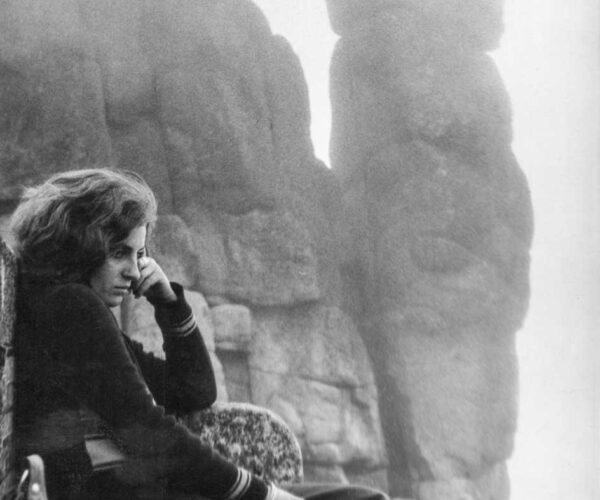

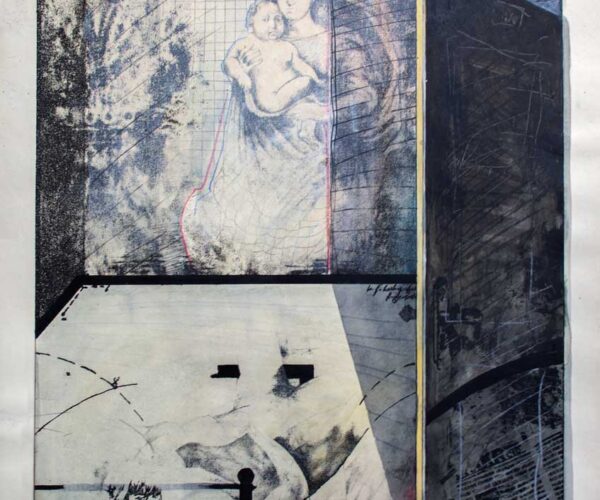

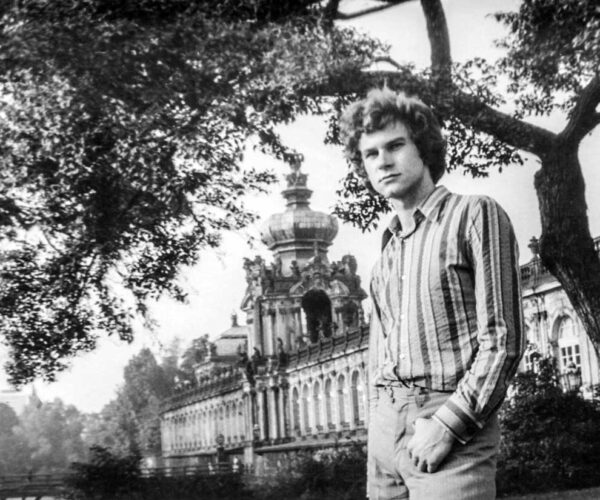

The holiday of 1974

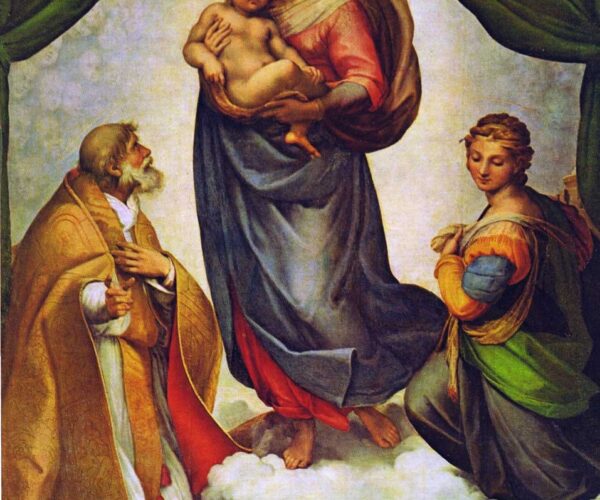

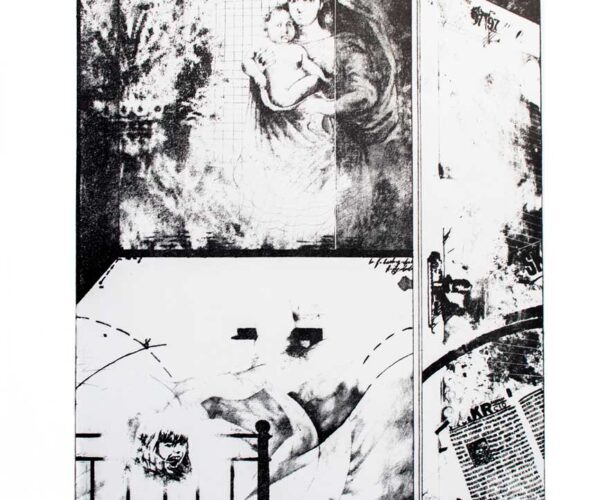

The first journey with my then-girlfriend (my love) Jolanta Mirecka was to Karpacz in the Karkonosze Mountains, where we explored all the possible mountain trails. Later, we traveled by train to the GDR: on our first trip abroad, which took us to Dresden. While on the train, we met a super-nice young German couple who immediately invited us to stay in their home. Our main goal in Dresden was t visit the Old Masters Gallery, but to our despair, it turned out to be closed. However, when the guard saw our long faces and heard my good German, he let us in – it was just us in the giant building. So, we could contemplate the masterpieces in peace. We were most impressed by Raphael’s Sistine Madonna – bewildered, we stood before it for over half an hour. We returned home warmed by the friendliness we had experienced from various people in Dresden and East Berlin. At the Academy of Fine Arts where, at the lithography studio, I was working on a cycle based on the short stories by Cortazar, The Sistine Madonna got incorporated in one print of the series; I saw a link between the picture and Cortazar’s short story entitled Condemned Door.

August 1975

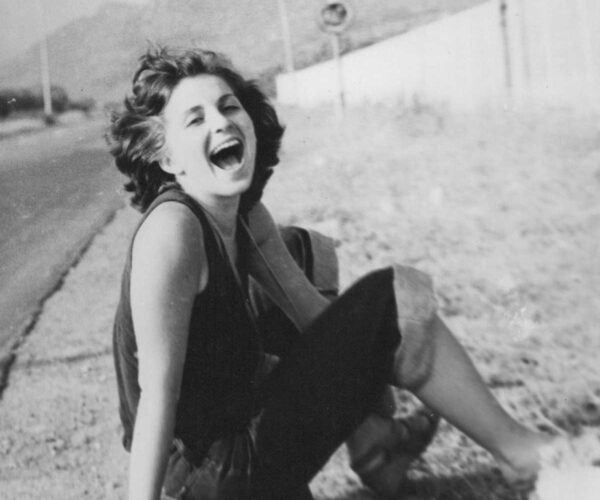

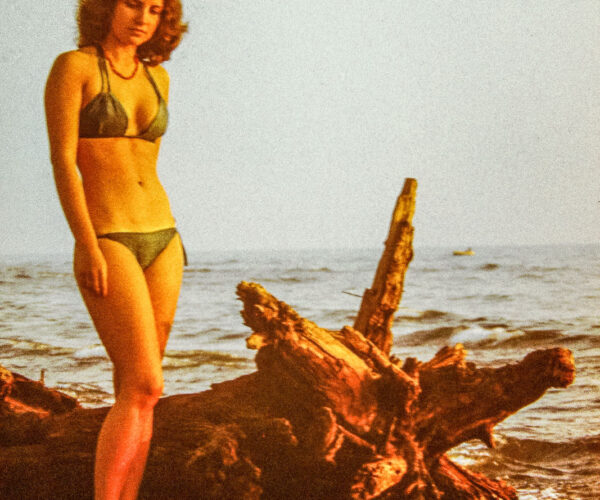

Before our wedding, Jola Mirecka and I embarked on our second journey abroad. Having crossed Ukraine by train, after two days, we reached Varna in Bulgaria – and got terribly disappointed with the crowds on the beaches of Golden Sands, so we moved further South, looking for a place to meet our expectations. On the way, we visited the amazing Nessebar and, after a few days, reached a campsite called “The Dolphin” close to Ahtopol, located on a thirty-meter embankment over a spectacular sandy beach. We put up our little tent close to the embankment’s edge and happily went to sleep. At night, we suddenly felt we are flying. We rolled across almost the whole campsite, and when we opened the tent, it turned out that the only reason why we had not fallen down the embankment was because the wind was blowing towards the land. It was raining horizontally, and the waves were hitting the embankment so hard that the breeze traveled thirty meters up – apparently, it was the storm of the century. “The Dolphin” got cut off from the land and became an island. After two days, the military picked us up in amphibious vehicles and took us to an accommodation in Ahtopol, where on the next day, we woke up to cloudless skies and fantastic weather. So, we returned to “The Dolphin” to stay there for almost two months of heavenly vacations. The beach and the campsite were practically empty; it was only towards the end of our stay that we met a young Polish couple (Ela and Piotrek Latała, with their son), who told us about the village of Varvara, just two kilometers away from “The Dolphin.” They were surprised our price for the campsite was two times what they were paying for accommodation in a private house in the village. Then they showed us Varvara, and the following year saw the beginning of our love for the place where we later spent more than twenty holidays.

October 1975

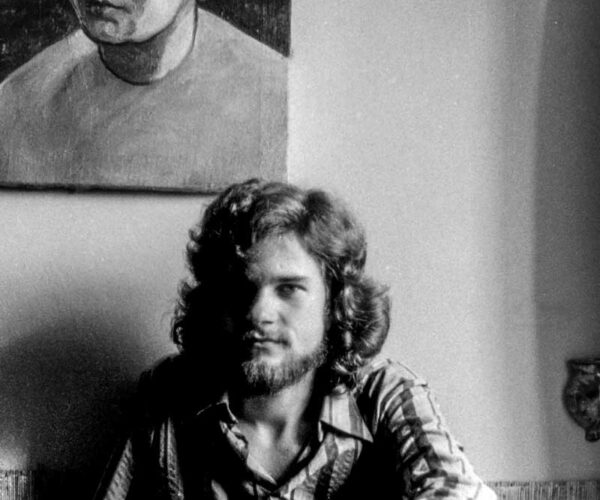

Only Prof. Stanisław Poznański in Warsaw was unconcerned by this negative opinion of mine (others gave a negative opinion of my application for transfer to the Academy of Fine Arts in Gdańsk because of this letter). I started studies in the Faculty of Graphic Arts, in the Painting Studio of Professor Stanisław Poznański and Lithography Studio of Professor Marian Rojewski. The former (Professor S. Poznański) was quite a good traditional painter, faithful to the canons of “colourism”, and an outstanding pedagogue. And the other one (M. Rojewski) was a party (PZPR) activist at the Academy of Fine Arts and had little idea about art. I came to Poznañski after my travels to Dresden and Berlin, where I was able to see the works of the old masters of painting in many museums and galleries, and I was convinced that I had absolutely no chance of approaching the level of the old brilliant Italian or Dutch painters in my painting, because I was completely smitten by their magic of colour.He restored my faith in my painting potential. I came to him after my travels in Western Europe, where I was able to see the works of the old masters of painting in many museums and galleries, and had the conviction that I had absolutely no chance of approaching the level of the old brilliant Italian or Dutch painters in my painting, because I was completely taken aback by their magic of colour. I returned home with a deep conviction that I have no chance whatsoever to even come close to this level in my painting – so I stopped painting altogether – I made pencil drawings and black-and-white graphic works. And even if I painted, these were actually monochromatic works (white-black-grey). Interestingly, I sold most of these works and they are appreciated by many until today. I have a problem with it until today: because I don’t like banal colour compositions – which come easy – and looking for original colours continues to be an ‘uphill struggle’ – it happens that it sometimes works, just like that, but more often than not I need months of trials and errors – but, paradoxically, recently I’ve been painting more and more colourful pictures.

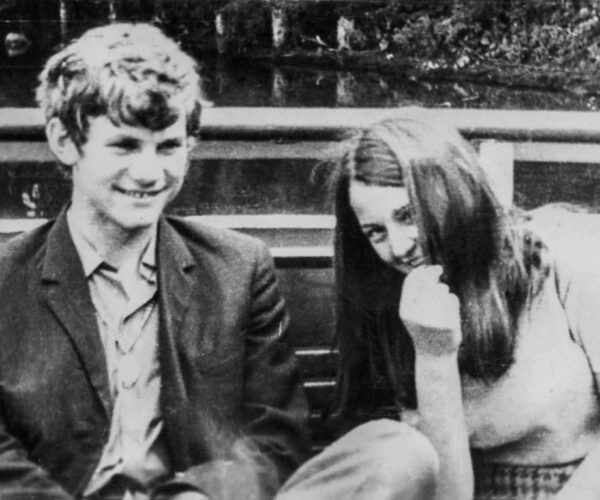

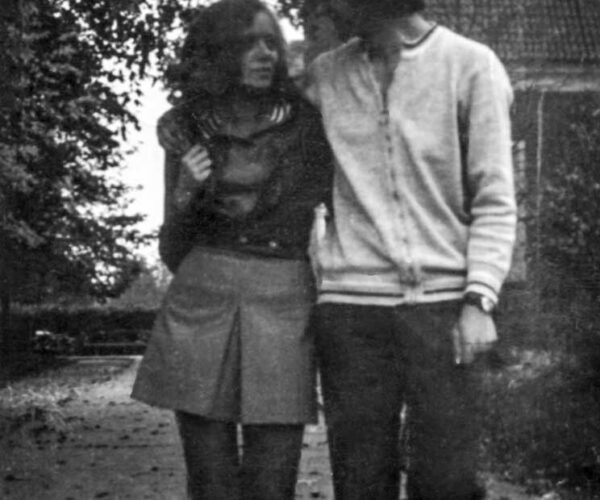

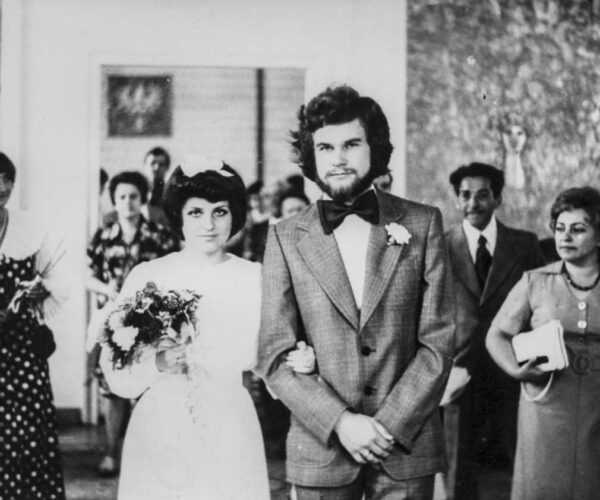

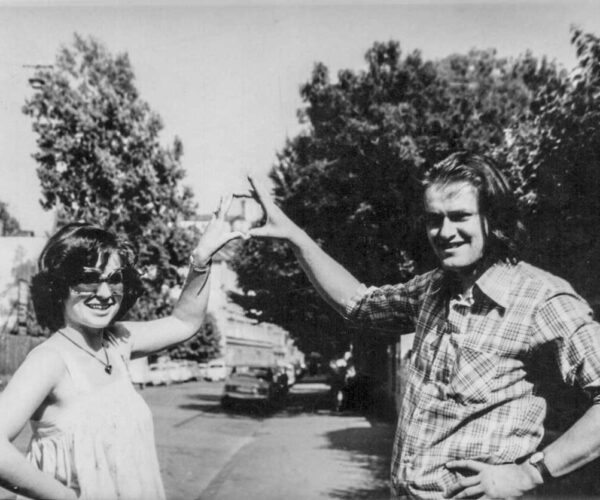

10 July 1976

I married Jolanta Mirecka (she decided to change her surname after our marriage to Niksińska), whom I had met while I was still a student at Przasnysz Secondary school. What was a certain phenomenon, we were united not only by love (almost from the first glance) or her beauty, but, what became very important for us, we had the same views on most issues. We liked the same things and we liked (or disliked) the same things in art, cinema, theatre, literature and poetry. The situation that she studied psychology at the Jagiellonian University in Krakow and I at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw was unacceptable to us in the long run, so on 10.07.1976 we got married so that Jola could move to Warsaw. I am also writing about it here because without Jola’s help, her understanding and tolerance of my artistic plans and problems, my biography could have looked much worse. So I am very grateful to her for being by my side all these years.

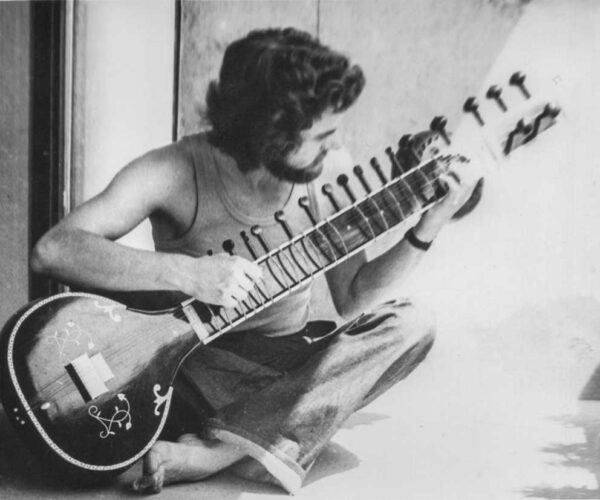

The Holiday of 1976

Invited by my friend Zdravko Papiĉ, we spent our honeymoon in his place in Ljubljana (Yugoslavia). Zdravko was a fellow student at the Academy of Fine Arts and the person who encouraged me to use acrylic paints, which were rather rare in Poland at that time. As a result, I started painting colorful pictures again. Earlier, I had used oils, and as my technique consisted in applying multiple semi-transparent glaze layers, it took ages before the previous layer dried. Acrylic paints dried instantly, but many of the Academy’s staff were extremely critical as they believed those paints would quickly fade and flake. Yet I still have many of those acrylic pictures, some of them forty years old and still going strong. After the visit to Ljubljana, we hitch-hiked across Yugoslavia, through Split and Dubrovnik as far as Kossowska Mitrovica, to reach the Bulgarian border and then Varvara, where we stayed in an old house with a beautiful garden. The owner was Baba Dafina – the only Christian in the area. Again, we stayed there for the rest of that holiday. While in Varvara, I made what was probably my biggest artistic discovery – in a forest close to a Christian temple, I found some reeds which looked like thin bamboo sticks. I used them to make various installations on the rocks – as they made a characteristic counterpoint for the said rocks. Based on the compositions, I took multiple photos and painted pictures. In 1988, I showed them all at my exhibition at the Institute of Modern Art in Nuremberg, and almost all were sold. Varvara has been inspiring my art until today, not just with these sticks but mostly with its special charm and atmosphere.

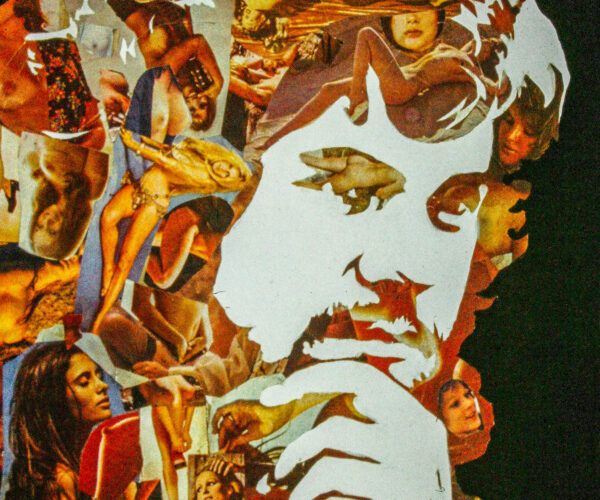

June 1978

I graduated with honors from the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw and showed two diploma exhibitions – a series of 12 lithographs “Landscape of almost no meaning”, where I wanted to show the relativizing flow of time for our memories and consciousness. The second exhibition was painting and showed a series of paintings that were specific conversations with artists and their works from the past and present (it concerned various fields from painting through music, literature, theater, cinema and poetry). After graduation, due to distinctions in my diploma, I received a one-year artistic scholarship from the Ministry of Culture and Science.

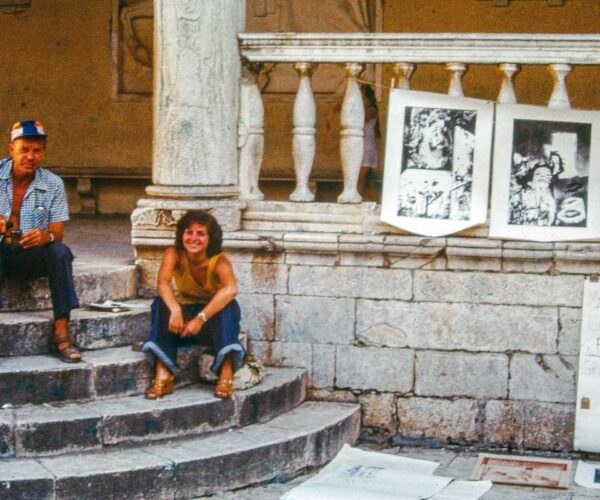

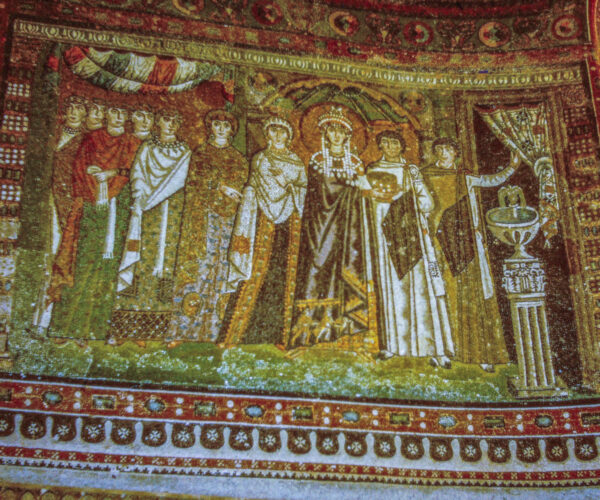

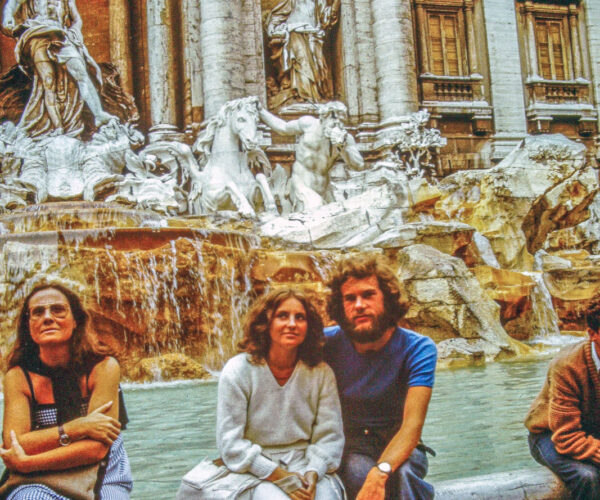

Trip to Italy

The summer after my graduation at the Academy of Fine Arts, my wife and I went on our first trip to Italy. When we arrived by train at Venice-Mestre station and looked around, we were a little heartbroken to see the ugly surroundings of the station and some industrial buildings, but when we walked through the station and the doors to the canal and old Venice opened up, our “jaw dropped”. We saw such a fairytale landscape with old Venice architecture and gondolas and water trams cruising the canals, it felt like we were in some kind of fairytale. After booking an overnight stay in Venice-Mestre, we boarded the Water Tram and took it to old Venice. Our first impression of the fabulousness of this architecture deepened for us with every step. It seemed to us that we had ended up in some kind of theatre and were far from reality and reality. Never afterwards has any city made such a magical impression on us. We wandered around the city into the night and got so lost in the narrow streets and canals that we barely had time to catch our last water tram to our flat in Mestre.

Having learnt from last year’s experience of auto-hopping around Yugoslavia, we hitchhiked to Padua after visiting Venice. It took us a long time, however, and in Padua we found out at the train station that trains in Italy cost so cheaply (it cost us about £20 for a ticket from Padua to Siena) that it was completely unprofitable for us to bother to risk hitchhiking further. So we travelled the whole of Italy as far as Tarquinia outside Rome by train. After seeing many paintings by old masters of Italian painting in the galleries of Venice, Florence or Rome, I was so enchanted by the colour of these paintings and their brilliance that, upon returning to Poland, I was unable to bring myself to paint in colour for a long time. I then made a whole series of black and white pencil drawings and lithographs – also black and white or with the colour reduced to the maximum.

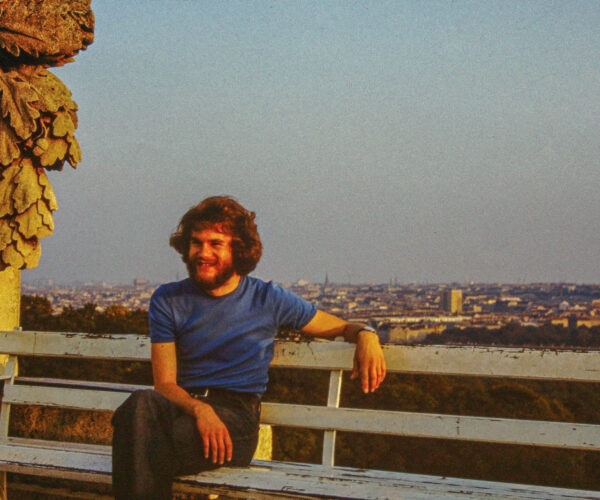

October 1979

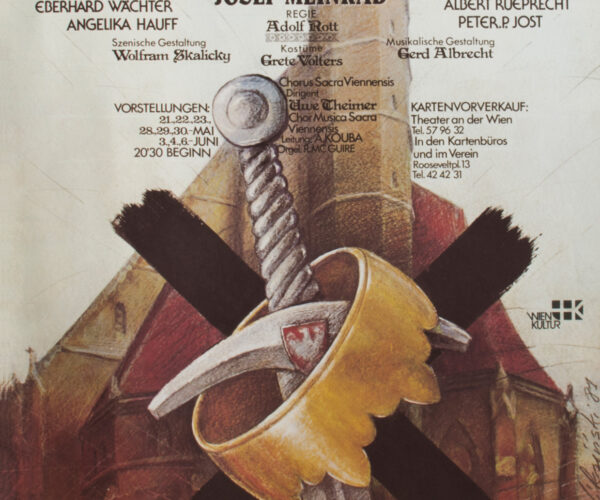

I also received an artistic scholarship in Vienna, where for 10 months I attended the Akademie für Angewandte Kunst and took a postgraduate master class with prof. Unger. There I learned about the latest lithographic techniques and made two new prints on aluminum plates, not on lithographic stones as before. My stay in Vienna also resulted in my next great discovery. There, in an art store, I found thin Japanese paper – tissue paper that becomes transparent when wet and can be used to add various interesting textures to paintings – I still use this technique today. Moreover, in Vienna I came across Angelika Hauf’s theater. She was then one of the most famous Austrian actresses. She bought one of my paintings and then offered me to design a poster for her new performance and to participate in it as an extra. Thanks to this, I met the leading actors of the Burgtheater, and I also visited most of the most beautiful churches in Austria, because the action of this theater takes place in a church and Angelika Hauf decided that it would be performed in real churches, not in theaters. This experience significantly expanded my knowledge of theater.

15 May 1980

That is the date of birth of our son, Marcin Niksiński. Unfortunately, his childhood coincided with the last decade of communism in Poland, with its ration coupons and empty shop counters. Back then, none of us believed communism would ever end.

13 December 1981

Introduction of Martial Law in Poland – When I returned from my art scholarship in Vienna at the beginning of October 1981, no one would have guessed that the “Solidarity Festival” would end so quickly and tragically. In Vienna, I made a lot of artistic contacts, but as martial law blocked all phone connections in Poland, and we didn’t even hear about the Internet, all these contacts got broken – some of them, I have not managed to recreate until today. All the artists I knew were boycotting Polish Television and offers of exhibitions (particularly abroad). At that time, I began receiving phone calls from the Ministry of Culture, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Television, and the Radio. I was astonished that someone at the Ministries found my phone number, as they had never telephoned me before – and did not telephone me later. They were calling with numerous offers of exhibitions at Polish Institutes around the world and offered to manage my career through galleries and museums. The Polish Television wanted to interview me and make a film about me – I only accepted the last proposal as I thought that martial law would probably be over before the film was finished. They sent an extremely nice journalist, Elżbieta Dryl-Glińska, and we made the film in my apartment and studio. Many years passed before I met Ms. Dryl-Glińska again, at a vernissage – I didn’t even recognize her, but she reminded me she had made a film about me – a fact I had completely forgotten. It turned out the communist censors had blocked the film’s release, and later, when Poland was free again, Polish Television lost interest. Maybe it can still be found in some dusty archives? Also, I have serious doubts as to whether turning down the offers of exhibitions was the right decision because many artists who accepted them became very successful. Today, no one remembers the decisions they made, and no one blames them.

During Martial Law we had a New Year’s Eve party at our house. At that time in Poland the telephones were switched off and I don’t even know how we managed to invite our friends and various acquaintances to our party – it spread via the so-called “grapevine” and a lot of people turned up at that New Year’s Eve party – even people we didn’t know at all and there was always a new doorbell ringing, which worried us a lot because we were afraid that it was the militia coming to arrest us, but new people kept coming, attracted by the sounds of our party. At that time, our flat on Stalowa Street had tiled cookers and it was very cold outside – over 20 degrees minus. It got very cold around noon, and I started to burn those cookers, but somehow it didn’t want to warm up for a few hours, so I kept adding more and more coal to our cookers. In the evening, when the guests started arriving, we had a real sauna, so we spent the whole New Year’s Eve with the windows open. When, after midnight, we all started singing “Let Poland be Poland”, you could hear it in the street and in the yard. A lot of windows in the neighbourhood were then opened and people joined in our singing.

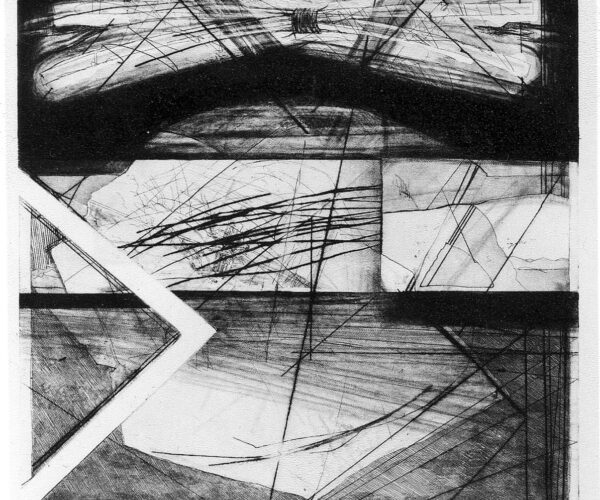

July - August 1982

Work at the Sommerakademie in Salzburg. From Professor Hradil, with whom I studied in Vienna, I received an offer to work with him as an assistant at the Summer Academy of Art. I also got this job thanks to my acquaintance with Barbara Wally – the director of this Academy, whom I met during my first stay in Nuremberg. This proposal reached me during martial law in Poland. During this period, it was not possible to obtain permission to travel abroad and I had absolutely no chance of obtaining a private passport. So I was forced to apply for a Pagartu service passport. Thanks to an invitation from Salzburg, I received such a passport, but it was subject to numerous conditions and difficulties. Among other things, I was supposed to write a report about my stay in Salzburg for the Security Service, but I didn’t do it – without any consequences. At this Academy, I made my only graphic using the “drypoint” technique and titled it “I’m afraid to live”.

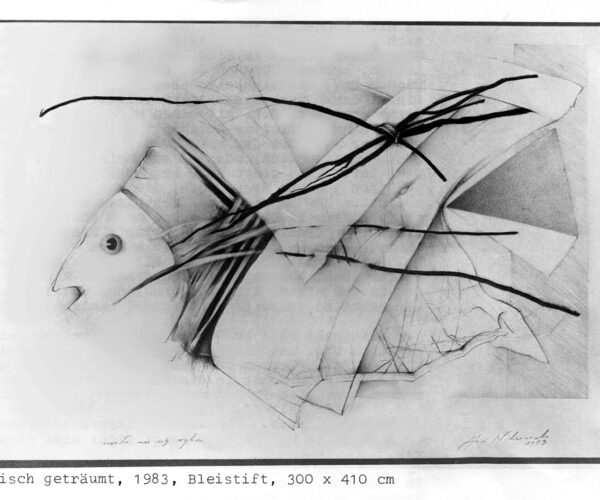

December 1985

Art scholarship from the city of Salzburg. Also thanks to Barbara Wally, I was also offered a month-long art scholarship in Salzburg, where I prepared for an exhibition at the Varisella Gallery in Nuremberg, and one of the drawings created during this stay (“and I dreamt of a fish”) was bought for its collection by the city’s Rupertinum Gallery.

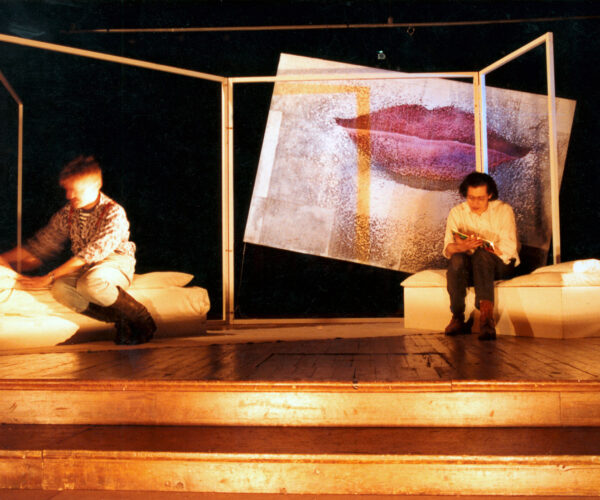

1990

Collaboration with THEATERmëRZ in Graz (also from 1991 to 1994) together with Willi Bernhart I produce many theatrical productions – “Fraktats”). The collaboration with this director was one of the most important artistic events in my life. Willi (Bernhart) called me with a proposal to work with his theatre as a set designer and theatre graphic designer. When I told him that I had never worked with any theatre before and that I had not done any theatre scenography, and besides, theatre, so far, interests me the least of all types of art, he said that

he had seen my exhibitions and catalogues and had enough of trained scenographers already and wanted me to do scenography with him as I paint my paintings. He suggested I design him a poster for a new show and a new business card for the theatre, as well as a new logo for his theatre. He liked my logo design and poster very much and then I came to see him in Graz. He then hired me as an assistant set designer to do the set design for his current show. The aesthetics of this set design did not suit me very well, but there was certainly valuable technical experience for me in creating this set design. Our meeting in Graz resulted in him proposing that I design (on my own) a set for Witkacy's play In a Small Manor House – he laughed that he had engaged a large Polish crew for this production and that Ewa Błaszczyk and Mikołaj Grabowski would be playing for him, the costumes would be designed by Irena Biegańska, and the music would be composed by Jerzy Satanowski, and if I also did the set design for him, he would have a complete Polish group. His fondness for Poland stems from the fact that, as a teenager, he came across Witkacy's plays and other texts, and was so enchanted by them that he wanted to learn Polish in order to get to know them in the original. During his studies in Vienna, he attended a Polish language course and then also tried to get an artistic scholarship in Poland and studied at the film school in Łódź. He also did many performances in Poland in many Polish theatres. When I met him, it turned out that he spoke Polish almost like a native Pole.

I was very hesitant to work on this production of “In a Small Manor House” but when Willi didn't ask me for any mock-ups or sketches, he just wanted me to take part in rehearsals and build something right away on stage, this work started to go relatively easily. Especially since it turned out that, when it came to the play, Willie and I understood each other almost without words. The production and my minimalist set design were such a success that he (Willi) offered me a permanent, further collaboration. We subsequently did 6 or 7 performances together. I write more about this in my catalogue “Transcendence of the Image”.

Trip to Italy

1993

Collaboration with Atelier Spieserhus began with my completely accidental meeting during my stay on a scholarship in Vienna with Agnieszka Jankowska, who bought one graphic from me and later became one of the most important collectors and promoters of my art. After studying in Vienna, many years later she moved to Rheinfelden near Basel, where she continued working at La Roche. Her friends in Rheinfelden were Mr. and Mrs. Hans-Jacques and Madeleine Keller, who ran Atelier Spieserhus there. In this Atelier, they showed off their huge collection of African art that they had accumulated during their many years in Africa. In addition, they regularly organized exhibitions of modern art, where they showed the work of contemporary artists along with thematic fragments of their African collection. Thanks to this acquaintance with Agnieszka J., they also invited me to organize two exhibitions where my paintings were shown together with puppets from Africa. Then they ordered a series of drawings from me based on the photographs I took there and organized my next exhibition with these drawings.

My paintings, prints and drawings made in collaboration with Atelier Spieserhus can be found on my website under collections – exhibitions, paintings, prints and drawings

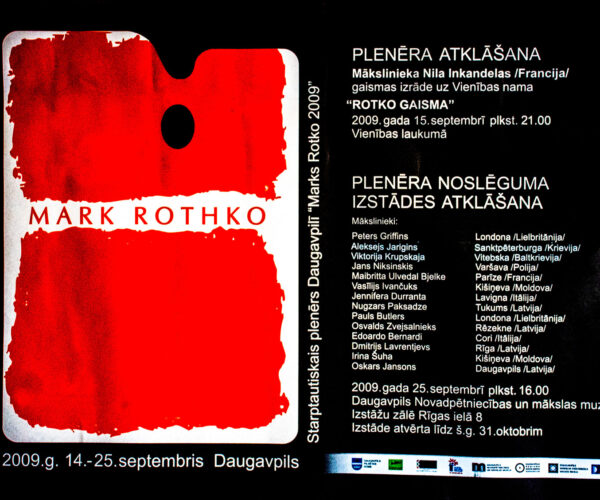

2009

International Plein – Air Mark Rothko – Daugavpils (Łotwa). I certainly owe my trip to this plein-air event to Marek Radke (a Polish artist who has been living in Germany for many years), who had previously been to this plein-air event and highly recommended the trip to Daugavpils. I also think that he put in a good word for me with the management of this plein-air event, because there is always huge competition from artists from all over the world. Rothko’s painting is very important to me and I think it has always inspired me in terms of the use of color, because he painted in a brilliant way in such a way that colored spots ceased to be paint and became color. For me it was definitely the most interesting, best organized, simply the best outdoor event in my life. A group of selected artists from all over the world were treated there like celebrities, we were provided with individual studios with full painting equipment (easels, brushes, paints and stretchers with primed canvas), an apartment in the best hotel in the city with a full bar, as well as interesting trips around the area, meetings with artists, critics and Latvian media. I also had the opportunity to see some very interesting films about Mark Rothko there. Then I painted a whole series of paintings that were my attempt to talk to this artist. For example, I painted the painting “Rothko on the Warwar Beach” outdoors and it is now in the collection of the Daugavpils Mark Rothko Art Center.

27 May 2009

Our first granddaughter, Zuzanna, daughter of Marcin and his wife, Magda Niksińska, was born, one day before my birthday. Interestingly, she is the first girl in the Niksiński family. From her earliest childhood, she has demonstrated phenomenal artistic talent, and her works frequently inspired my paintings. So far, we have even painted one picture together – “Child’s Flowers at the Sea.”

11 December 2012

Our grandson Jędrzej Niksiński was born, an outstanding little individual. I am very curious to see how he will turn out in the future.

2015

I participated in a discussion about Poland’s two most famous theaters: the Theater of Tadeusz Kantor and the Theater of Grotowski. I was invited to join by Bogdan Wrzochalski, the then deputy director of the Institute of Polish Culture in Vienna, as an expert on Tadeusz Kantor’s Theater, which, since the premiere of The Dead Class, has shaped my definition of modern theater based on tradition and individual originality, and my entire later philosophy of art. It was also an important factor in my multiannual cooperation with TheaterMëRZ of Willi Bernhart, who, in his theater, to a considerable extent used the methods of Kantor’s Cricot. The discussion occurred during a festival of plays by Sławomir Mrożek, which the Polish Institute organized in many theaters in Vienna. The Institute also published a book entitled „Es war ein Leben, kein Schauspiel” (which translates as: “It was Life, not a Play”) in which all the speakers, including myself, could present their thoughts and experiences related to theater.

2017

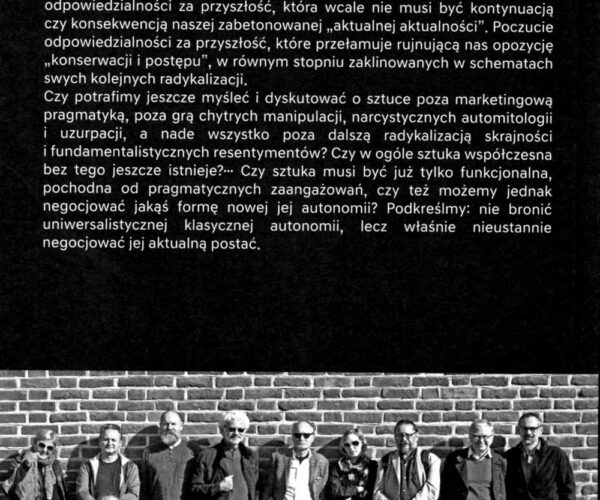

I participated in the Forum of New Autonomies of the Arts organized in Elbląg’s Galeria EL, by Sławomir Marzec – author of the idea of Autonomy of Art. Marzec asked me to present one of my pictures and write a text for the book, published under the above title, to mark the occasion.

FNAS declaration

The established New Art Autonomy Forum is a kind of experiment, bringing together people with very different views and interests on an ad hoc basis. But critical of the growing unification and monopolistic practices of the (especially domestic) artworld. What unites us is a sense of responsibility for the future, which does not necessarily have to be a continuation or consequence of our hardened “present”. A sense of responsibility for a future that breaks down the ruinous opposition of “maintenance and progress”, equally stuck in the patterns of their successive radicalisations.

Are we still able to think and discuss art beyond marketing pragmatics, beyond the game of sly manipulation, narcissistic self-mythologies and usurpations, and above all beyond the further radicalisation of extremes and fundamentalist resentments? Does contemporary art even still exist without this?… Does art have to be merely functional anymore, derivative of pragmatic engagements, or can we nevertheless negotiate some form of its new autonomy? Let us emphasise: not to defend a universalist classical autonomy, but to constantly negotiate its current form.

The aim of the Forum for New Artistic Autonomies (FNAS) is to activate concern for the autonomy and quality of art

- the FNAS calls for genuine pluralism: there is not just one art, but an infinite variety of arts; in fact, everyone needs art to his or her own measure

- the FNAS fights against functionalisations, appropriations and monopolisations of art (also local and ad hoc). Contemporary art has the status of an experiment and no one has the right to impose the “only right, current or worldly” interpretation of it

- the FNAS promotes art rooted in individual subjectivity, engaged in an existential and cultural game of meaning

- the FNAS opposes the reduction of art to the role of a collector’s gadget, a mass media event, political indoctrination, but also narcissistic self-therapy or so-called sociability

- the FNAS stands in opposition to artworld, which has ceased to be a field of free discussion and has turned into a monopoly of the public redistribution of the idea of art

- the FNAS stands in opposition to the toxicity and mediocrity of mass culture and it is not so much the capacity for adaptation and socialisation that becomes important, but precisely the capacity for resilience, the capacity for independent and polemical practice of culture or art.